https://www.pricevaluepartners.com/forever-doesnt-last/

“Almost all [of us] own a smartphone or a computer.

Each device contains the library of Alexandria.

The sum total of all world knowledge.

You can learn anything. Why don’t you?

Too busy tracking social status.

Too enthralled by imagery your evolution can’t resist.”

Tweet by @TheStoicEmperor.

And he’s right. Our friend Tony Deden, one of the smartest and most principled men – and asset managers – that we know, makes precisely the same point:

“Even at a time of personal computers, instant communication, fancy cell phones and the miracle of the internet, and even when surrounded with more information than any of our ancestors ever dreamed of, we as a society remain in utter darkness. Compared to our ancestors, we are intellectually bereft. We know nothing of our own history, of money or capital. We see money and credit as the source of wealth. We embrace financial engineering while being uninterested in or ignorant about its economic impact. We embrace the idea of wealth without work and even demand it. We buy other people’s debts and we call them assets. We demand real goods and plentiful credit to pay for them. We look at rising asset prices and reckon them to be wealth. We vote idiots into high office. We hail economic growth, as measured by GDP and by the clipped coins of our time, and hail it as progress. We are a society of idiots.”

One of these trends may soon go into abeyance. Those “rising asset prices” now look a little less than secure. While the backdrop to the global investment marketplace is one of bond yields rising from 5,000 year lows, the current concern for many investors is the recent weakness displayed by the share prices of Big Tech.

This has been a long time coming, and we can’t say we weren’t warned.

As we all know, the latest outcrop of the “wall of worry” that stock markets in a bull run habitually have to climb consists of the so-called ‘Mag[nificent] Seven, i.e. Big Tech (the likes of Nvidia, Facebook / Meta, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Broadcom and Google / Alphabet).

We are not saying that any of these companies is a bad company (well, with the possible exception of Facebook, which we consider a waste of time indulged in largely by vanity publishing millennials). We use Apple products every day. We use Google products every day. We give money willingly to Amazon in one form or another at least every month or so, and more likely once a week. They all offer tremendous service – and Amazon’s customer fulfilment is second to none.

But there is a difference between a quality company and a successful investment. The key ingredient which is so often missing from the recipe is price. At a low enough price, almost any investment will work out over the medium term. But at a high enough price, almost any investment has the potential to be a disaster. The problem with the Mag 7 is that so many of them are already so priced for perfection, they offer little or no realistic margin of safety.

And we have seen this story before. Older subscribers may remember that we saw this movie in the 1970s. Back then they weren’t called the Mag 7 or the FANGs, but rather “the Nifty Fifty”. The idea behind the Nifty Fifty was that they were “one decision stocks”: the only question was which one to buy. And then one simply had to hold it forever.

The problem being, forever didn’t last. Chris Pummer picks up the story:

“Unlike typical “buy-and-hold” stocks such as slow-growing but generous dividend-paying utility-company shares, investors were willing to pay unbounded prices for a piece of the Nifty Fifty pie.

“That optimism was visible in a key measure of the stocks’ value: the price-to-earnings ratio or P/E – the price-per-share divided by the company’s annual earnings-per-share. By 1972 when the S&P 500 Index’s P/E stood at a then lofty 19, the Nifty Fifty’s average P/E was more than twice that at 42. Among the most inflated were Polaroid with a P/E of 91; McDonald’s, 86; Walt Disney, 82; and Avon Products, 65.

“Along came the stock market collapse of 1973-74, where the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 45% in just two years. It was driven by the end of the Bretton Woods monetary system, soaring inflation and the first of the 1970s oil crises. As a Forbes columnist described it, the Nifty Fifty “were taken out and shot one by one.” From their respective highs, for instance, Xerox fell 71 percent, Avon 86 percent and Polaroid 91 percent.”

Humanity seems destined never to learn from its experiences. Perhaps it comes down to the limitations of a lifetime: by the time the next generation comes along, they are ready to make all the same mistakes that their parents did.

The 1970s gave us the Nifty Fifty, some of which are still with us today, so they weren’t a total bust.

The late 1990s (almost exactly a generation later) gave us the first dotcom boom, and all the same mistakes were repeated.

In the pitches that we sometimes make to investors, we often highlight the fate of the dotcom darlings. Different circus, same clowns.

Why are we so often dismissive of the financial media ? Because so often they are also idiots.

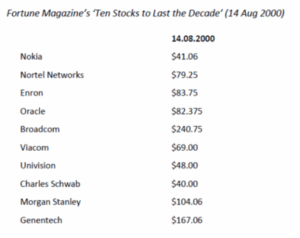

A now notorious issue of Fortune Magazine, published in August 2000, recommended Ten Stocks to last the Decade. Those stocks, and their share prices, are shown below.

As befits the dotcom boom, there was heavy representation in the Fortune portfolio by telecoms and digital media (Nokia, Nortel, Broadcom, Viacom, Univision), by finance (Charles Schwab and Morgan Stanley), by biotech (Genentech) and by fraudulent scams (Enron).

How did the Fortune portfolio fare ?

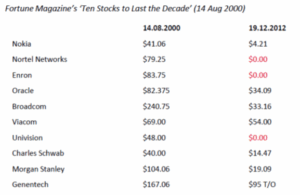

The results are shown below.

In aggregate, the portfolio lost 65% over the subsequent decade or so. Three of the companies went bankrupt outright. One of them, Genentech, got taken over at a much lower level. There is a timeless message here. It is difficult to buy what is popular and do well. Or, if you prefer, in investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable. Not a single stock in Fortune’s portfolio was worth more at the end of the decade than at the beginning. The magazine achieved something quite incredible: a 100% failure rate.

To adjust the second quote just a touch, it doesn’t mean that we are obligated to seek out only those investments which we find distinctly uncomfortable (though that in itself might well lead to superior returns, for those investors with the constitution to bear it). Rather, at a minimum, we should feel comfortable at least heading down the road less travelled, because there is more likely to be hidden value in sectors and regions that the herd has overlooked. But the key missing ingredient will always remain price.

We suspect that the tech sector has further to fall this time, so we wouldn’t yet be planning to catch any falling knives. There will undoubtedly be winners among the fallen, but we’re not bright or technologically savvy to know which ones they are. And in a world in which President Trump gets to pick fights and engage in publicly damaging point scoring versus anyone and anything, we have to conclude that anything is now possible. The Overton Window is now almost infinitely large.

On the topic of Facebook, consider an excellent book by one of its earlier employees, Antonio García Martínez, called Chaos Monkeys: mayhem and mania inside the Silicon Valley money machine. It’s both insightful and wonderfully well written, with a cynical wit that we find hugely appealing. But it also offers some early insider perspective about the practical growth limitations of the company. The following extract dates back to March 2012:

“The reality is that Facebook has been so successful, it’s actually running out of humans on the planet. Ponder the numbers: there are about three billion people on the Internet, where the latter is broadly defined as any sort of networked data, texts, browser, social media, whatever. Of these people, six hundred million are Chinese, and therefore effectively unreachable by Facebook. In Russia, thanks to Vkontakte and other copycat social networks, Facebook’s share of the country’s ninety million Internet users is also small, though it may yet win that fight. That leaves about 2.35 billion people ripe for the Facebook plucking.

“While Facebook seems ubiquitous to the plugged-in, chattering classes, its usage is not universal among even entrenched Internet users. In the United States, for example, by far the company’s most established and sticky market, only three-quarters of Internet users are actively on FB. That ratio of FB to Internet users is worse in other countries, so even full FB saturation in a given market doesn’t imply total Facebook adoption. Let’s (very) optimistically assume full US-level penetration for any market. Without China and Russia, and taking a 25 percent haircut of people who’ll never join or stay (as is the case in the United States), that leaves around 1.8 billion potential Facebook users globally. That’s it.”

Now there are plenty of things that you don’t want to see in connection with any growth stock, but the one paramount thing you actively never, ever want to see is any reference to potential market saturation. And Facebook, taking Martínez at face value, had already come close to reaching that point in 2015. The question isn’t really how far Facebook stock falls from here (we happen to think: potentially quite a lot), it’s why didn’t anyone appreciate these limits years ago ?

Please note that we’re not “talking our book here”. We don’t own Facebook, never have, and never will. By the same token we’re not short Facebook stock either. But as value investors, there are some things we’re just congenitally not well adapted to understand. And one of them is a naff, vanity publishing site that pimps out information provided freely by its many users in order to sell them stuff. We never really got the point of Facebook and have deactivated our presence there. It runs the risk of suddenly being regarded as not cool any more, and may well already have reached that point.

There is a hideous irony about the marvels of the modern digital economy. On the one hand, per @TheStoicEmperor and Tony Deden, we all have access to the library of Alexandria in the palm of our hands, at negligible cost. On the other hand, all this access, together with the insistent clutter of social media, blogs and the press, seems to be making us collectively less intelligent. The conclusion has to be that we must all get better at filtering the Niagara of information and data that continually cascades towards us, 24/7. We repeat our advice to restrict your information diet to only the most nutritious of sources, and to cut out the junk.

Just as there is merit in the discriminate selection of investments from everything that the world has to offer us, there is comparable merit in applying information filters to what we read and correspond with. Otherwise modern life is just a mad dash across an ocean of information, a million miles across but just a few millimetres deep. Perhaps the answer is, if nothing else, just to consciously slow down, and ignore the siren songs of the Internet and digital media.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and also in systematic trend-following funds.

I’d vote for Tony Deden in the role of “ Serene Emperor of the Known Universe”.

Great Work, Great Insights.

Thank You!

The problem is not the access to unlimited information in the palm of our hands, it is the excessive and second by second barrage of advertising perpetrated by charlitons, crooks and thieves that make most tune out the noise. Trust is a precious thing and "internet" is extremely poor at providing it.